Confederation of Indian Industry — Branding & Marketing Conclave 2018

Last month, I was kindly invited to speak at the above conference in Indore by the Confederation of Indian Industry. The audience included local entrepreneurs, marcoms professionals and students studying the disciplines.

I spoke about 9 shifts that are radically changing the way brands are and can communicate with their audience, before explaining how the application of one single piece of amateur psychology can help brands address and navigate the same. Let’s start with the 9 shifts:

- Meet the new Editors-in-Chief!

According to The New York Times, nearly half of US adults rely on Facebook as their principal source of news1; others cite Twitter as the real news source of the 21st century2. Such so-called alternative or ‘first person’ news sources are even more important to younger generations; 61% of US millennials source political news from Facebook, for instance, compared to just 39% for Baby Boomers3. With more people not merely sharing news but also exercising editorial control on what they share, we are entering the age of ‘peer-to-peer’ news. In some cases, this editorial influence is overt (“Hurray, Manchester United has won two games in a row”); in others it’s more subliminal through the use of emoticons, icons or, increasingly, memes, for instance.In both instances, the sharer is assuming an editorial role deciding, not merely what to share, but how to position it.

The nature of the Web is confrontational; people generally take sides before they enter into a conversation. Even the most partisan formal publication has an editorial code, a process for address and rectification, a mechanism for all parties to be represented in an argument. Commercial realities oblige publications to retain a modicum or integrity and factual veracity, if for no other reason than to maintain their advertising revenues. No such equation relates to pure ‘peer-to-peer’ news; within the laws of liable, people can say just what they like.

- The importance of ‘image literacy’

First person news is increasingly referenced by mainstream channels to complement broadcasting; the ubiquity of camera phones and videos render the recording of any event effortless, and social media does the rest. The expulsion of a hapless passenger from an overbooked United Airlines flight becomes global news when a video emerged of the incident4; it is hard to imagine ‘passenger bumped off full flight’ making headlines without the accompanying coverage.In essence, this was a purely visual story; made possible and defined by the associated video. But the latter doesn’t reveal the whole story, the various offers made to passengers to switch flights, the fact that the passenger had actually re-boarded the flight after being expelled (in contravention of US civil aviation regulations); the practice of overbooking is not limited to United and – it could be argued – fundamental to helping maintain low fares.

In reality, just 0.004% of United Airlines passengers were involuntarily bumped from flights last year. None of these facts excuses the treatment received by this unfortunate passenger, but it does illustrate a key shortcoming of ‘first person’ reporting; the lack of context. By definition, such first person ‘peer-to-peer’ reporting is always ‘one eyed’.

- The algorithm; it actually works both ways

Facebook uses 98 data points to fine tune (unsolicited) advertising; but this selection is from a total of potential 29,000 insights the platform has on its users. Everything from wedding anniversaries and employment history, to shopping habits and relationships... All designed to make user experience (and the barrage of unsolicited advertisements) more meaningful and relevant; of course!But there is a corollary to all this data-fuelled fine tuning — the degree to which a brand can personalise its message to a consumer is equal and opposite to the ease with which that consumer can block that message. That’s the brutal truth about algorithms — they work both ways. Today:

- 59% of smartphones in India come equipped with adblockers as standard

- 61% Indian smartphone users already employing ad blockers; 122 browsers equipped with ad blocking software

- The latest version of Web browser Chrome now comes equipped with ad filters

- A word from the competition

This is the brutal truth about today’s communications environment.Boo was one of the first dogs to really make it big on the internet. His owner set up a Facebook page in 2009 with photos of the adorable Pomeranian dressed up in different doggy outfits, showing him getting into mischief with his pal Buddy (his Pomeranian partner in crime). Before long, this famous Pomeranian was dubbed “the cutest dog in the world” and his page now has over 17 million likes. Unfortunately, it was announced that his pal Buddy passed away in September 2017 at the age of 14.Maru is an adorable Shiba Inu who lives with his owners in Japan and is one of the most followed dogs on Instagram with over 2.6 million followers. And these are just dogs. I haven’t even included cats, or parrots! But such cuteness is actually competing with your brand on people’s timelines; and no amount of product messaging or, even paid advertising, is likely to make any difference.Ok – fine for consumer brands, but B2B brands are not going to be impacted surely?

In the US, for instance, 59% of organisations allow employees to use their own devices for work purposes, 87% of companies actually rely on their employees using personal devices to access business apps. Bring your own device (BYOD) is becoming ubiquitous; so yes, even B2B brands are competing with Boo and Maru for attention!

- The University of Twitter and the ‘Di Maio effect’

Follower count is the new, post-modern PhD. It’s worth more than academia, sporting prowess, or practical experience. This is a relatively new phenomenon which politicians, brands, and academia are still struggling to reconcile with their hard-earned credentials. When the Morandi Bridge collapsed in Genoa, Italy, earlier this year, Italy’s vice president, Luigi Di Maio, wasted no time in apportioning the blame squarely on Autostrade per l'Italia, the private organisation charged with maintaining the infrastructure. No reference was made to the original design (from 1967) and whether it was adequate for the speed, nature and volume of traffic 50 years later.

Neither was any reference made to scientific or architectural reports highlighting material faults in the bridge a year before the tragedy.On what basis was Di Maio able to make such assertions; what exactly are his architectural, engineering, or geological qualifications? He graduated from the University of ‘Twitter’ of course (451,000 followers). Di Maio boasts no formal qualifications or documented expertise. He didn’t even graduate from University, despite studying first engineering and subsequently law. So, in effect, someone with fewer credentials than an engineering intern is able to identify the causes of a structural collapse of one of Italy’s most iconic bridges, even before any enquiry has even started!

He may be proved right, of course, but the point I’m highlighting is that, today, credibility and influence is not necessarily a function of qualifications in the conventional sense, but of reach.It’s crucial for brands to appreciate this phenomenon; their reputation is less likely to be determined by dedicated, informed experts, than so-called uninformed but extremely influential consumers. And this influence is typically concentrated in to distinct moments which represent a huge risk/opportunity for the brand.

- Consumers are the new protagonists

Affordable Internet – and, particularly, mobile, has removed the final last barrier to mass communications; today, it’s the public who set the agenda, who decide what’s trending, who determine – not only what counts as news – but how that news is conveyed (positively, negatively, with indifference). And given a choice between news about brands, or about them as individuals, the latter would win every time.

We are entering a new era of brand relationships; one which is no longer defined by the brands, but by individuals themselves – whether they be consumers, employees, investors, collaborators or members of the local community. Today, these individuals are the protagonists in news, conversations and content; they define, propagate, legitimise the subjects of interest; they are the new editors-in-chief of today’s news. For brands, we are entering a type of ‘post-protagonist’ age; the control and influence which brands used to enjoy through control and access to the media has dissipated. Now, brands’ best hope is to ensure sufficient relevance to enter into other people’s conversations; it is the latter who have become the real protagonists.This dynamic is possibly a more traumatic shift than the previous ages described above; particularly for brand managers accustomed to driving conversations and owning the media. In a post-protagonist environment, the new criterion for brands is to become an ‘extra’ in the lives of others. Brands that accept and embrace this shift will enjoy a deeper engagement with their public. Those that resist will become irrelevant.

-

- Sharability is not for sale

The dynamic of peer-to-peer is incredibly powerful; it beats every other form of endorsement. This is my favourite example:Luis Fonsi’s song Despacito went through Universal Music’s usual promotional channels before transforming into a Youtube phenomenon, generating over 4 billion views and counting. Much of the popularity was organic – Despacito even become a terrace anthem for fans of the Argentinean team, San Lorenzo (Luis Fonsi is actually Puerto Rican which is over 6,000km away) – but trying to extract the respective contributions of paid verses genuine organic is an impossible task.However, brands must consider this cold, hard reality; given the variety and volume available, people only consume content (whether it be a video or a newspaper; a radio emission or a piece of theatre) for three basic reasons:

-

- Entertainment; to be amused, gratified and satisfied. Content could range from sport to soap opera, from documentaries to newspaper articles, but the consumer’s primary motivation is amusement; to be stimulated and enjoy the experience.

- Information; whether the content be educational or practical (traffic or weather reports), the basic motivation is driven by necessity.

- Prestige; with the advent of social media (particularly mobile) content has become a form of social prestige, and sharing the same a means to derive prestige. There is considerable research on the subject; suffice it to confirm that the act of sharing is not simply altruistic; it generates benefits (social and other) to the emitter. The combination of content which is both (perceived to be) prestigious and shareable starts to become extremely compelling, but when it comes to virality, there are still no guarantees.

The great unwritten law of social virality is the idea of gratification – and I don’t mean the brand’s. I mean the audience’s. Why should they share your content? What is their incentive to participate in your campaign? Motivations can range from prestige (especially with content that is somehow ‘exclusive’ or ‘private’) to monetary (offering discounts to people who participate in your campaign), but the key is to provide some form of acknowledgement to your audience; it is they, who are going to propagate your message after all.

My ‘earned/editorial’ instincts tend to favour the ‘prestige’ approach to gratification; if you can create genuine value for your audience (premier access to a product or service), exclusive interaction with a celebrity, or some form of public recognition (the ‘super fan’ logic), there is an opportunity to develop valuable relationships that last.

Personalisation has become the ‘social currency’ of the age. People – particularly younger audiences – are systematically more likely to share content that they can make their own, to which they can add their spin, their identity. The beauty of Donald Trump’s accidental ‘covfefe’ Tweet, published last May, was the ease with which people could personalise it, and contribute their take – and gratification – to the whole episode.

And the brand in all of this? The paradox is that virality is rarely dependent on the brand, it is actually all about the audience. This is one of the characteristics of the ‘post-protagonist’ age in which brands are operating. So the best response to the client ‘viral video’ request is to start studying your target audience as quickly as possible.

- Relevance beats any USP or how to compete with a talking dog

In a world dominated by peer-to-peer influence, by studied and guarded indifference by consumer, by jealously protected timelines, and infinite levels of content to choose from, relevance is a brand’s best chance of breaching the ad-blockers and engaging the audience.Such relevance is unlikely to be a function of the product – think of who we are competing against for their attention (yes, that’s Boo the talking dog, again!). Relevance is about the audience; what they are concerned about and how they are feeling. The key for brands is to connect with that.

- What we can learn from celebrities

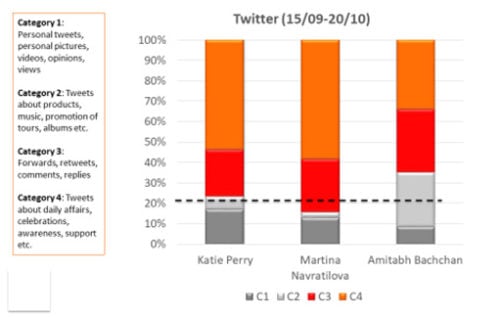

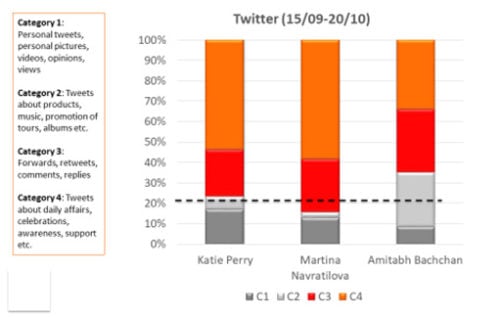

They really are smarter than the rest of us! Referring to an indicative — i.e. not exactly scientific — study (see above) from 2017’s Twitter feeds of a celebrity pop star, a sportswoman and an actor, we can clearly see their understanding of today’s communications reality.

In the analysis (above), categories 1 and 2 refer to content about the individuals themselves (their events, their music/films, merchandise etc.), while categories 3 and 4 refer to their response and opinions on external events; in short, the rest of the world. On average, our celebrities spent only 20% of their time talking about themselves, the rest about everyone and everything else.

Celebrities have understood the value of relevance; the more they associate with the world which their audience inhabits, the greater the degree to which they’ll be able to influence them. And brands which appreciate this logic will enjoy the same benefits.

Noisy Neighbour Logic

Which brings us neatly to the piece of amateur psychology required to navigate the above – ‘Noisy Neighbour Logic’. The more you talk about yourself, the less other people will; the more to talk about and relate to your audience, the more they’ll talk about you.

We’ve all experienced the egocentric neighbour whose conversation never ventures beyond the success of his progeny, his golf handicap, his amazing pension plan, or the killing he made on the stock market. You know the type. Other people’s conversation is simply a trigger for him/her to talk about him or herself. Bizarrely, some brands behave in exactly the same way! Social media is simply the aggregation of human behaviour; so, firstly, listening and making yourself relevant to your audiences’ conversations should be the (only) starting point.

Only brands which take the trouble to find out about what their customers actually care about, and make themselves relevant to the same, will be included in people’s conversations.

And, in an age of media disruption and disintermediation, only brands which really listen will be best placed to engage their audiences like never before; whether those audiences be consumers, employees, partners, regulators, investors, or other members of the community.

This is the simple but powerful lesson from Noisy Neighbour Logic.